Railroad Workers Across the Nation Go on Strike: July 16, 1877

- Catholic Textbook Project

- Jul 14, 2025

- 2 min read

This text comes from our book, The American Venture.

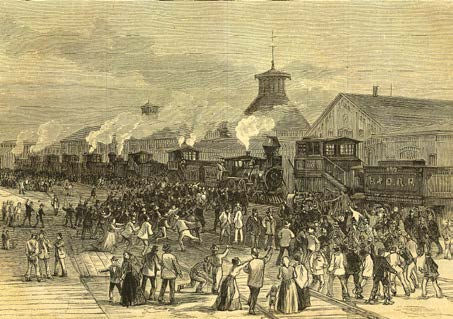

One month after the 19 Molly Maguires were executed, railroad workers in Baltimore went on strike. Railroad workers’ wages had already been so low that they could scarcely support their families, but the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had announced that it would cut their wages further. The workers pleaded with the railroad’s owners, but to no avail. Finally, on July 16, 1877, the workers refused to work. Soon other railroad workers from West Virginia to St. Louis, Missouri, joined the strike, and railroad transportation, as well as industrial production in the North, ground to a halt.

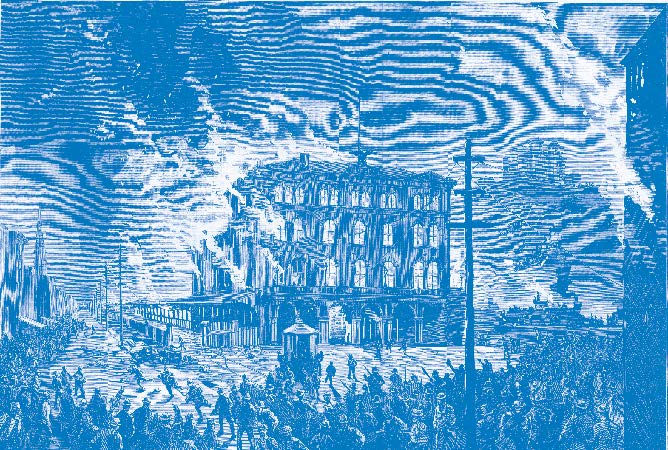

The “Great Strikes,” as they came to be called, brought unrest to the cities. Not only railroad workers, but tradesmen and women and young girls formed angry mobs and destroyed railroad property. In Pittsburgh, the killing of 16 men and children by state militia ended in a battle between workers and militia and a looting of the city’s businesses. By the end of July, coal workers had joined the strike, cutting off that important supply of fuel to industries and foundries that relied on it.

The workers “insurrection,” as it came to be called, appalled Americans who did not belong to the number of those on strike. They feared that socialists and communists had instigated the violence. Some thought the workers had no right to complain; were not their wages but a sign of their inferior abilities? Were they not just getting what they deserved? An old anti-slavery leader, the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, told his congregation at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York, that the workers could live on their low wages if they were content to subsist on bread and water and did not “insist on smoking and drinking beer.” Workers indeed, said Beecher, had the right to withhold their labor, but they must understand that economic laws “could not be set at defiance.”

The demonstrations in Pittsburgh ended only when, in late July, President Rutherford B. Hayes sent the U.S. Army to support the state militia. The presidential intervention effectively marked the end of the strikes that, in Pittsburgh and throughout the country, had left hundreds of millions of dollars in destroyed property. In the wake of the strikes, companies continued to cut wages and suppress attempts by workers to form unions to fight for their rights.

Still, though the Great Strikes did not achieve the workers’ goals, they were not an utter failure. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad promised pensions (half wages) to workers who were ill, had died, or had been injured while working. The Pullman Palace Car Company built a town for its workers outside of Chicago. Such benefits, however, were far less than what the workers had demanded. The strikes showed that, if workers were to succeed, they needed leadership and better organization. Random strikes and violence could not contend with the organized power of the industrialists and the government.