A Christmas Present for Old Abe: December 22, 1865

- Catholic Textbook Project

- Dec 18, 2020

- 4 min read

This text comes from our book, Lands of Hope and Promise: A History of North America.

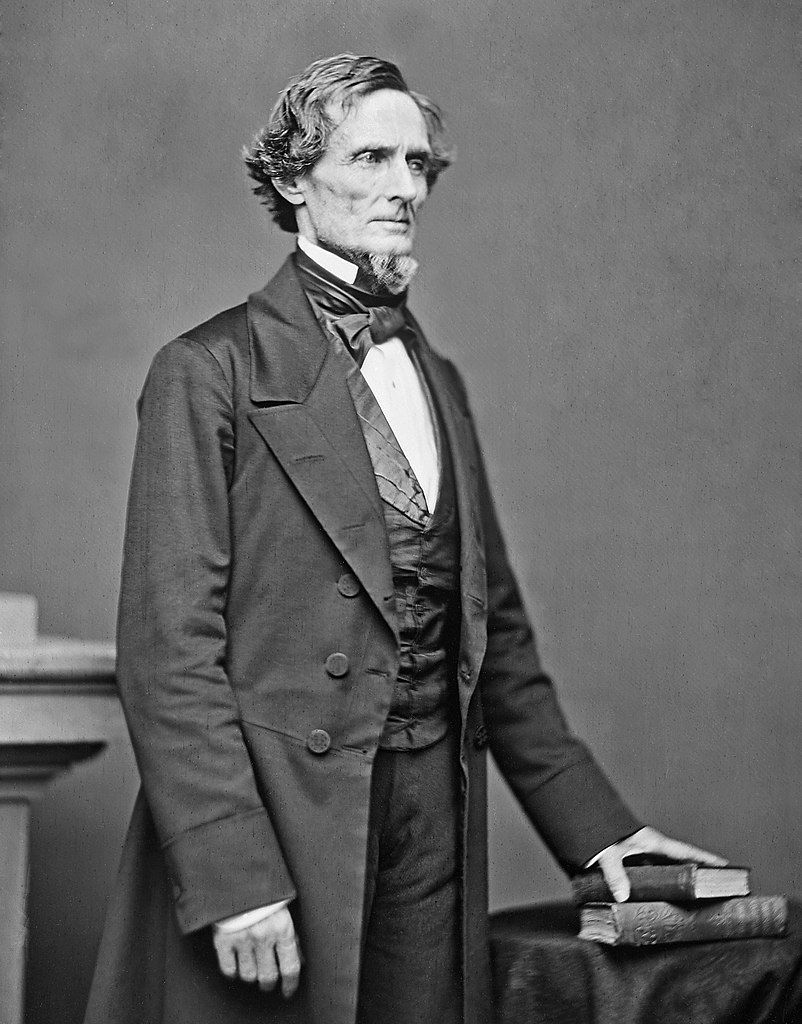

On November 7, 1864, the day before the northern elections, Jefferson Davis addressed the Confederate Congress:

“There are no vital points on the preservation of which the continued existence of the Confederacy depends. There is no military success of the enemy which can accomplish its destruction. Not the fall of Richmond, nor Wilmington, nor Savannah, nor Mobile, nor of all combined, can save the enemy from the constant and exhaustive drain of blood and treasure which must continue until he shall discover that no peace is attainable unless based on the recognition of our indefeasible rights.”

These were brave words, but they betrayed desperation. They hinted at irregular, guerrilla warfare continuing until the North grew so tired of blood that it would concede southern independence. The regular channels of government in the South were fast falling apart. Even in the face of Sherman and Grant, some Southern governors obstructed the Confederate draft; the governor of Georgia said it violated states rights. The armies were in desperate need of soldiers, and records showed that from 100,000 to 200,000 men were absent. Davis had gone to Macon, Georgia in September to appeal to men to return to duty, but to no avail. As one Confederate senator from Texas noted, the people’s “confidence was gone, and hope was almost extinguished.”

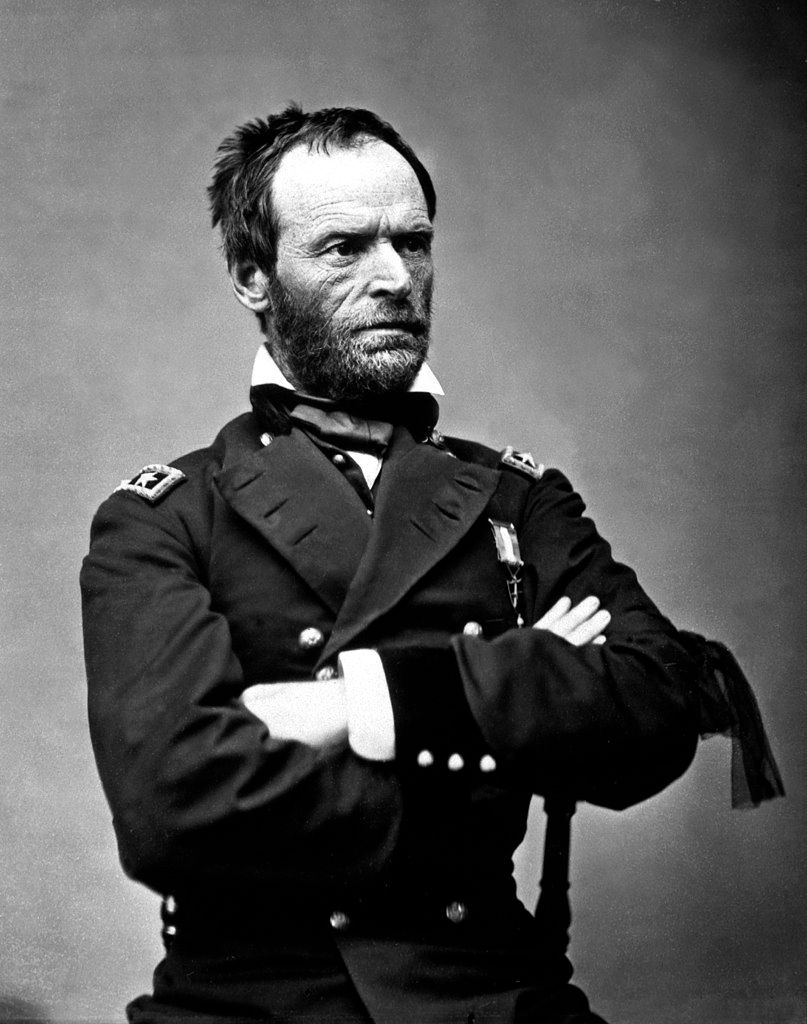

In this the twilight of the war, Federal generals were proving more relentless. In September, Sherman ordered all civilians to evacuate Atlanta and arranged a ten-day truce with Hood to allow them to pass through Confederate lines. Both the mayor of Atlanta and Hood protested; such an evacuation, they said, would bring heavy suffering to civilians, especially to the infirm and the old. “The unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war,” wrote Hood to Sherman. The Yankee general, however, was unmoved by appeals to antique chivalry. “Gentlemen,” he replied, “You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty and you cannot refine it . . . You might as well appeal against the thunderstorm as against these terrible hardships of war.”

When the civilians had evacuated the city, Sherman ordered one-third of Atlanta burned. Then, on November 16, Sherman left Atlanta behind, and with 60,000 of his men, began a march, eastward, to the sea. This was a daring act, for Sherman was cutting himself off from his supply base and from all communication with the North. He had conferred with both Grant and Lincoln before commencing this march, and both, though doubtful, had approved it. Sherman explained that his great army would live off Georgia’s rich farmlands. His goal was the seacoast town of Savannah, where he could reestablish contact with the North.

Hood did not follow Sherman. Hood assumed that if he threatened Tennessee, Sherman would follow him. Hood planned to march through Tennessee, into Kentucky, and go all the way to the Ohio. On November 30, at Franklin, Tennessee, Hood led 13 charges against Federals under Pap Thomas and suffered a bloody repulse, losing one-fourth of his army. On December 15, Thomas attacked Hood at Nashville and routed the Confederates. Hood’s army was splintered and destroyed, and a central railway hub fell to the Federals. The Confederate army of the West was no more. Only scattered cavalry units and militias were left to contend with the victorious Federal army.

Meanwhile, Sherman’s advancing columns were laying waste the countryside, plowing a furrow, 40 miles wide, of destruction. Sherman had ordered that his troops respect private property, but nobody (not even he himself) took his order seriously. Sherman had said he wanted to “make Georgia howl.” “We cannot change the hearts of these people of the South,” he wrote, “but we can make war so terrible . . . and make them so sick of war that generations [will] pass away before they again appeal to it.”

Sherman’s was a war of vengeance, rapine, and cruelty. What was not stolen was wantonly destroyed. “As far as the eye could reach,” remembered one woman, “the lurid flames of burning [houses] lit up the heavens. . . . I could stand out on the verandah and for two or three miles watch as they came on. I could mark when they reached the residence of each and every friend on the road.” Yankee soldiers stole from white and black alike. They killed so many cattle that “the whole region stunk with putrefying death carcasses.” Soldiers frightened white women, sometimes molesting them; black women were treated less kindly. “The cruelties practiced on this campaign toward the citizens have been enough to blast a more sacred cause than ours,” wrote a Federal corporal. “We hardly deserve success.”

Thousands of escaping slaves followed in the wake of Sherman’s army. They hardly dared venture too far from the Federal army for fear of roving Confederate militia and cavalry units who might return them to slavery or simply kill them. Within Federal lines things were not easy for slaves, either. Many Federal officers and men had no sympathy with freeing slaves. Disease, starvation, and exposure took their toll on hundreds of blacks.

For the duration of the march, neither Lincoln nor Grant had heard anything from Sherman. Finally, on December 22, Lincoln received a telegram. It was from Sherman: “I beg to present you as a Christmas present the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition; also, about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

With Hood’s army destroyed and Georgia devastated from Atlanta to the sea, only Lee’s army now stood between Lincoln and complete victory.

Weeping, Sad and Lonely

“Weeping, Sad and Lonely” was a song very popular in the North during the Civil War. Some Union generals, however, forbade it in the camps. They thought it demoralizing.